by Ralph Smith, Deputy Head of Public Health Information, Public Health, Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council

The future of some vital public health-related information hangs in the balance as a result of the ONS Consultation on Statistical Products 2013. The bland title of the consultation belies the rich and varied statistical products it covers. They are divided into four areas, with the last two representing the bulk of the products in question:

• Output from national surveys, such as the general lifestyle survey

• Regional and local outputs

• Health statistics and analysis, life events

• Health inequalities analysis

Respondents are asked to state what the impact would be of discontinuing the product and encouraged to expand on the consequences if an impact is anticipated.

There are some critical products on the list and I encourage public health professionals to take part in protecting them. Increasingly, policy documents are emphasising the importance of robust data sources and analysis, so it is an unfortunate time for ONS to be proposing cuts.

We are all going through a period where the provision of local public health analysis is under pressure due to a shortage of skilled staff, increased demand in a Local Authority environment and problematic relationships with the NHS over access to data. At the same time we are reliant on national organisations, such as ONS and Public Health England, to provide nationwide data produced through economies of scale.

The consultation document often refers to alternative sources of data to the one they are suggesting they may cut. But what happens if that alternative source dries up too?

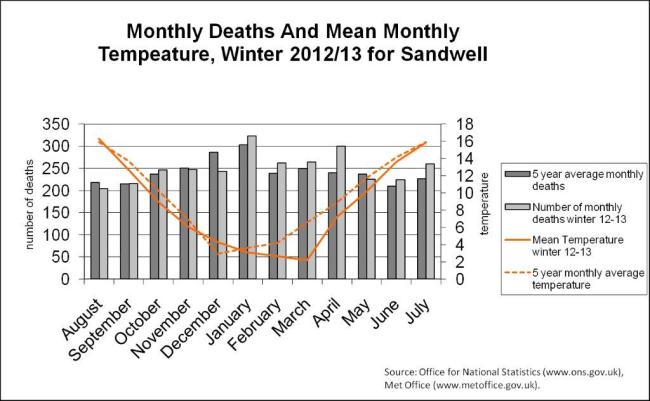

One proposed product to discontinue is the monthly reporting of death registrations. The monitoring of excess winter mortality relies on such data sources, both nationally and locally. Indeed Local Authority Public Health has its own supply of mortality data, via the primary care mortality database. What the national monthly data provides are vital comparators to help make informed analytical decisions in areas such as health and housing.

Figure 1: monthly death and mean monthly temperature, Winter 2012/13 for Sandwell

Winters may be getting warmer on average, but cold snaps are happening later in the season. Thus, austere conditions that influence a household’s ability to heat their home means that such health and housing topics are still very much on the agenda.

In the health inequalities section of the consultation, many of the products are vital to public health. They act as either a national benchmark to monitor progress, or provide small area analysis for local authority public health to reduce inequalities within their boundaries. Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy analyses were first commissioned from the Marmot secretariat. This small area intelligence was used to draw attention to the spread of health inequalities within an area, helping to target scarce resources. A refreshed update of these data is under threat.

Figure 2: Life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy at birth, by neighbourhood income level, England and Sandwell 1999- 2003

Figure 2: Life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy at birth, by neighbourhood income level, England and Sandwell 1999- 2003

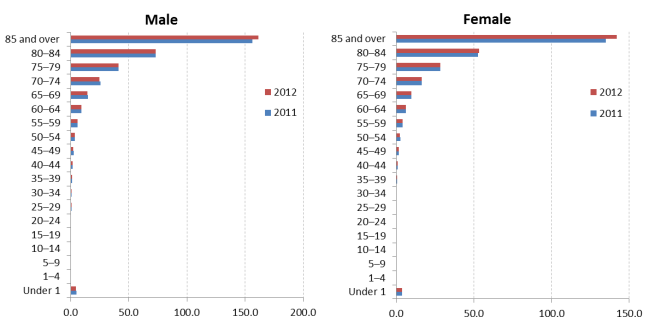

There are several products that take a closer look at health outcomes by protected equality groups such as occupation, deprivation and gender. Often there are no alternatives to such analyses.

Discontinuing the products outlined in this consultation does not only affect the professional public health world. The idea of using freely available datasets and presenting them simply and clearly is increasingly popular with the media, charities and the voluntary sector. The Guardian Datablog frequently uses ONS data to drive home a story.

Coupled with novel ways of presenting information, this brand of data journalism creates debate on current social issues. And it’s not only the broadsheets that use this method. The free paper the Metro frequently uses public domain national data to producer infographics such as the one below.

ONS are not looking to discontinue all the products listed in the consultation. However they are looking for users to help them prioritise statistical products, some of which have to be cut to help contribute to annual savings of around £9 million. I encourage you to take part in the consultation and emphasise how important the majority of the products are in influencing policy and informing interventions.